Editorial Note: This post is part of how to study the Bible (the complete series).

Bible interpretation is part science and part art. There are two phases that you’ll go through. The first phase is working to discover the original intent of the writer. And the second is to apply those ideas to our modern context.

While there are some varying guidelines for the different genres of writing in the Scriptures, there are a handful of common rules for Bible interpretation and study that should guide us. And that’s what we’ll be diving into in this lesson.

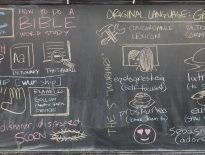

Discovering Original Intent

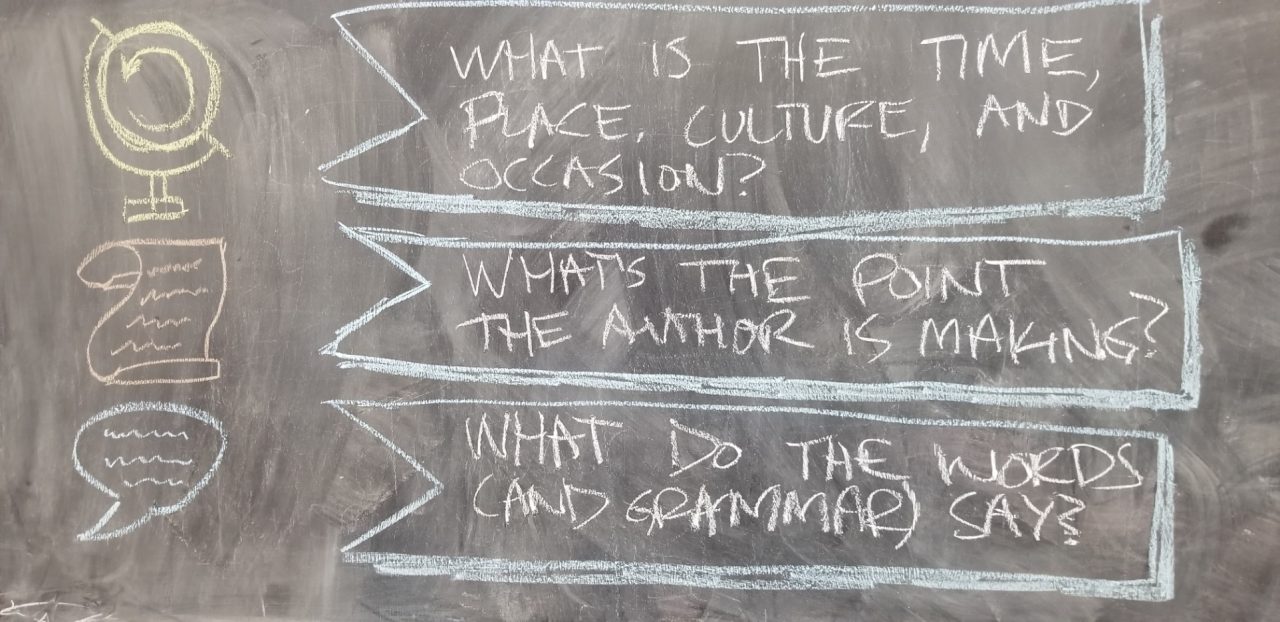

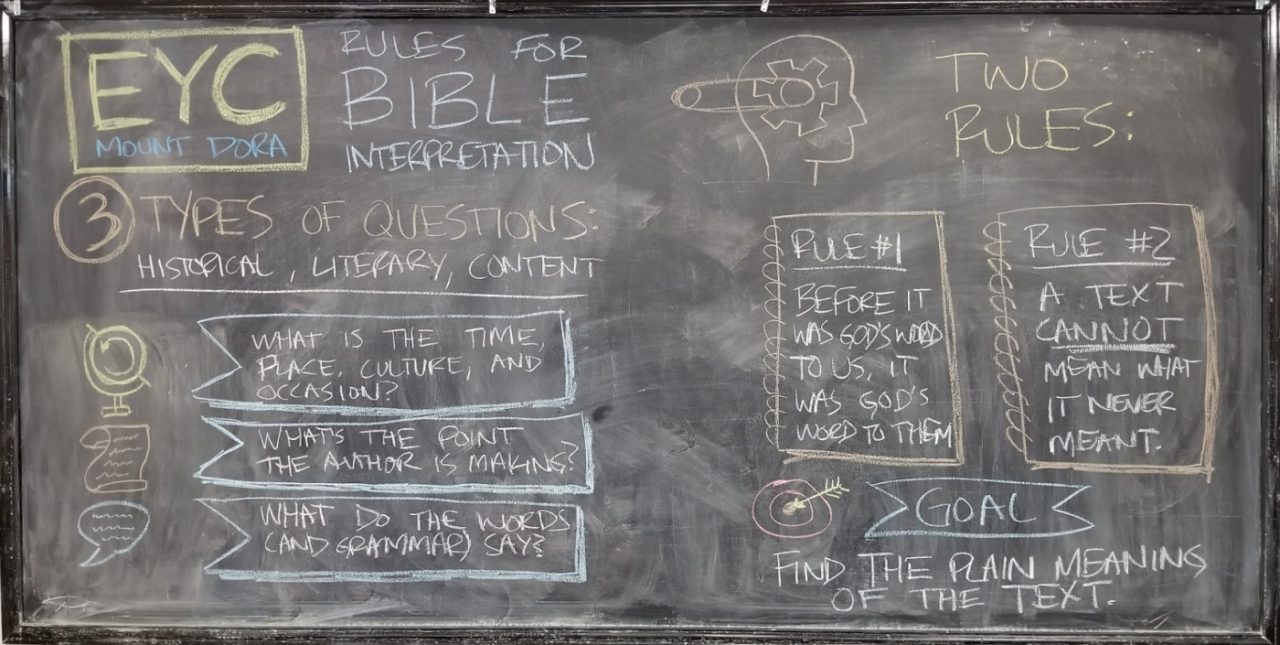

The key to intelligent reading of the Bible is (1) to read the text carefully, and (2) to ask the right questions of the text. And when you’re reading to understand the author’s original intent, there are two types of questions we ask. Those are questions of context and questions of content. Additionally, the questions of context come in two forms, historical and literary.

— Historical Context

In their book, How To Read the Bible For All Its Worth, Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart describe the question of historical context this way:

The historical context, which will differ from book to book, has to do with several things: the time and culture of the author and his readers, that is, the geographical, topographical, and political factors that are relevant to the author’s setting; and the occasion of the book, letter, psalm, prophetic oracle, or other genre.

My thoughts: This is about closing the historical distance gap. In order to fully grasp what the writer is saying, you need to know things like what’s happening in the time and place of the writing. Sometimes we can get this from the passage itself and/or from related historical texts in the Bible that speak to the current events of the people at the time. Another good source for this kind of information is commentaries and other historical writings.

One of my favorite examples of how the historical context shapes how we read the passage is with Jeremiah 29:11. It reads, “‘For I know the plans I have for you,’ declares the Lord, ‘plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.'” It’s easy to read that as if it was written to us and believe that God want’s us to have nice things… NOW.

However, when we dig into the occasion of Jeremiah’s letter, we see that it was written originally to a people going into exile in Babylon. And considering that they would be there for 70 years, it’s a word spoken to a generation who would only experience exile for the rest of their lives. While it’s accurate to believe that God wants us to prosper, we should also understand that it’s a vision that goes beyond our immediate circumstance. We may still encounter trouble, even for long periods of time. Because his promise of prosperity is not a promise of giving me comfort and wealth today.

Personally, I start to think about how all of my struggle and toil in this life will pay off in the long-run, especially with the legacy I leave for my children and my children’s children. So I try to avoid looking for a selfish prosperity.

— Literary Context

Regarding the question of literary context, Fee and Stuart say this:

The most important contextual question you will ever as—and it must be asked over and over of every sentence and every paragraph—is, “What’s the point?” We must try to trace the author’s train of thought. What is the author saying, and why does he or she say it right here?

My thoughts: The key here is that a passage cannot be taken out of context of the whole writing that it’s part of. You simply cannot take a single passage and try to interpret it by itself. Following the author’s train of thought, you must consider what the entire writing is about. For example, when Paul writes a letter to the Galatians, then you must consider the overall message of the entire letter. Any individual passage in the letter cannot contradict the message of the letter.

Additionally, these themes cannot contradict with the overall message of the Testament it appears in, or with the overall message of the Bible.

The best practice you can take is simply reading more (of the Scriptures). If you want to study a passage in one of Paul’s letters, then take the time to read the entire letter (maybe even a few times, in different versions/translations). This will help you understand the overall message so that you can more accurately identify what the author is saying in the passage you want to study.

— Questions of Content

With the question of content, Fee and Stuart have this to say:

“Content” has to do with the meanings of words, the grammatical relationships in sentences, and the choice of the original text where the manuscripts (handwritten copies) differ from one another.

My thoughts: This is where our word studies come in. Reading the text in multiple versions/translations can help with this. But ultimately, this is about doing the deeper dive word studies, both in English and in the original language. Word use is incredibly important. Consider these perspectives on word use:

- Genesis 1:3 – God speaks (uses words) Creation into existence

- Genesis 2:20 – The first recorded act of man was of him using words to name every animal

- Genesis 3:1 – First act of the serpent was using words to bring confusion

- John 6:68 – Jesus’ words have eternal life

Becoming a student of the word use in the Bible has the potential to bring us incredible insight into the message it brings.

Rules For Bible Interpretation

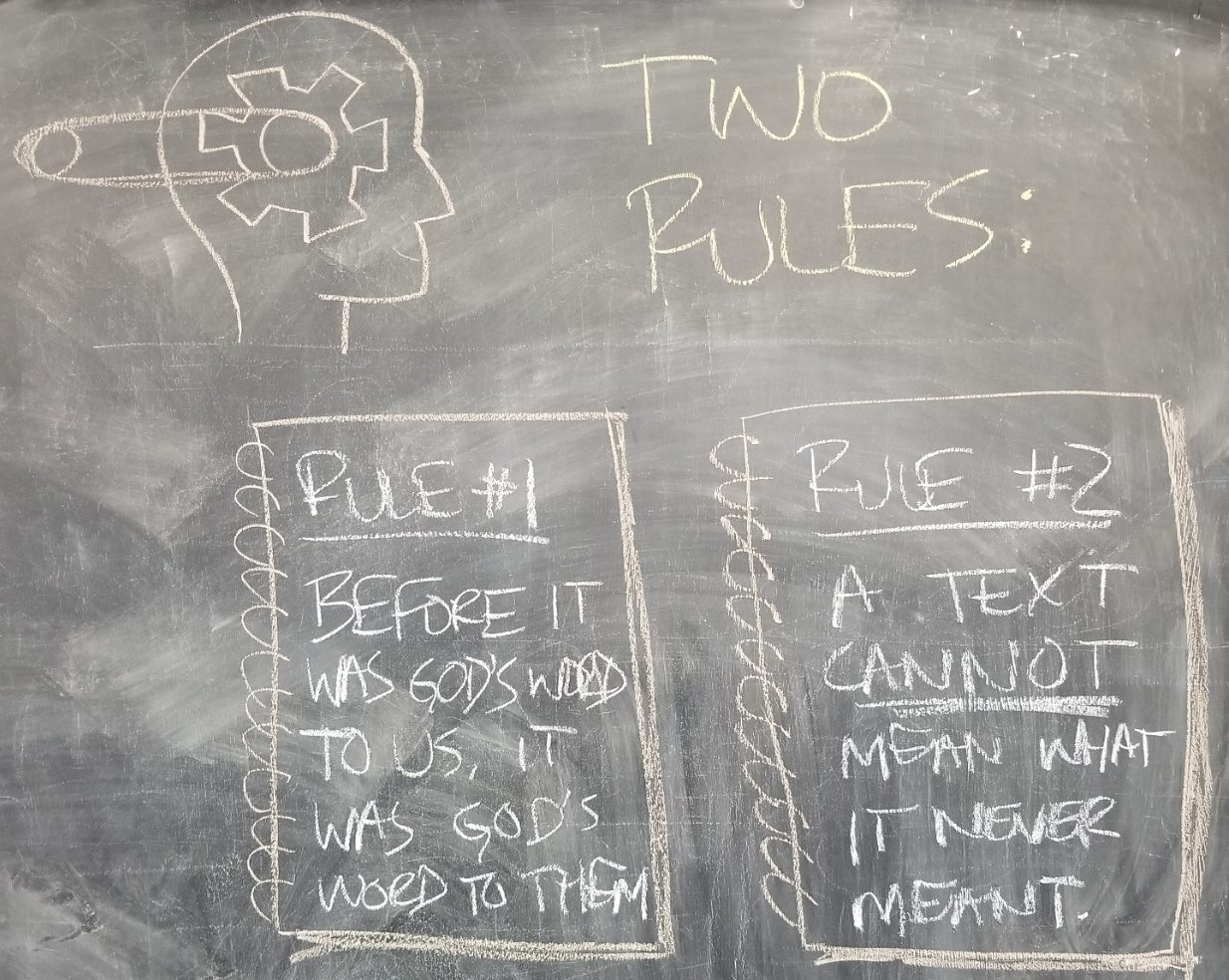

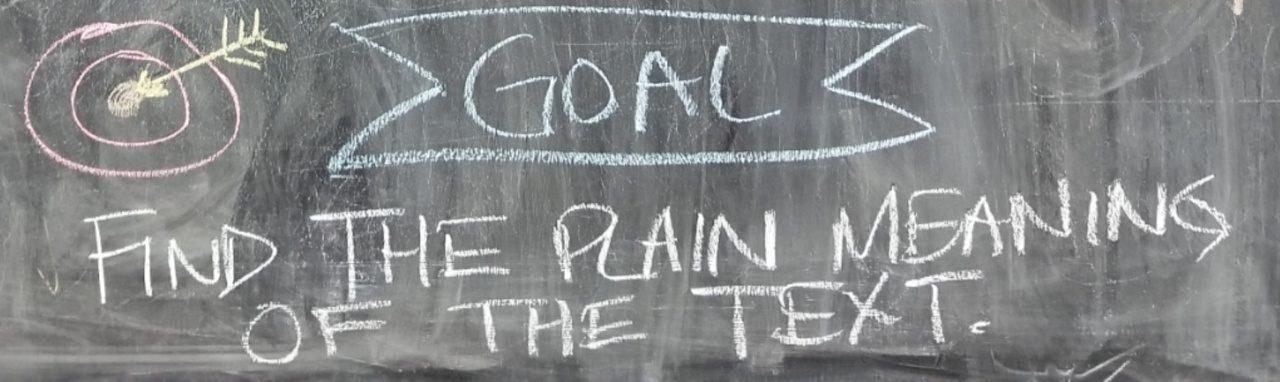

When studying the Bible, answering these questions of context and content help us to uncover the original meaning of the text (a process called exegesis). The next step is to then apply the principles to modern situations. This is the task of interpretation, or applying the Scriptures to our lives. When we’re doing this interpretation and application, there are two rules we must always remember:

- Before it was God’s Word to us, it was God’s Word to them. This is what drives our exegetical questions (context and content). While the Bible is certainly God’s Word to us today, we cannot forget that it was written in a context that wasn’t ours. Recognizing and understanding what God was saying to them can help us filter what it means to us in a completely different time and culture.

- A text cannot mean what it never meant. The Word itself doesn’t change. So we cannot twist a passage around to fit into what we want it to say in our context. And honestly, that’s a dangerous path to go down. Ultimately one could make the Bible say anything they want it to say, and to justify anything they want to do (and many have over the course of history). The text has a meaning, and that meaning doesn’t change (or contradict with the overall message).

Applying Bible principles to our lives and modern situations works best when you dig deep to understand what the texts are saying, find the principle, and apply that to our modern circumstances.

We deal with some hot topics in our culture today, like abortion and global warming. Does the Bible use either of those terms? No. There’s isn’t anything written that directly deals with those issues.

But the Bible does have a lot to say about the sanctity of life. We can pull principles from the Bible related to how Christians should live that would guide us on whether abortion is something we should consider.

We can also pull principles from God’s call for us to care for Creation that can guide us on the issues related to environmental care. Is global warming a real issue? Honestly, does it matter? We’re called to care for Creation anyway. And answering that call is in alignment with much of what people who want to limit global warming want to accomplish.

Final Thoughts

Careful examination and intelligent reading of the Scriptures can open us up to even greater insight into how to live the Christian life. Ask the right questions, and apply the principles thoughtfully. I also believe that these Bible interpretation not only helps with understanding, but it can also deepen your love for the Word of God.

0 Comments